Early Reminiscences.

by Harriet Newell Barney Stevens.

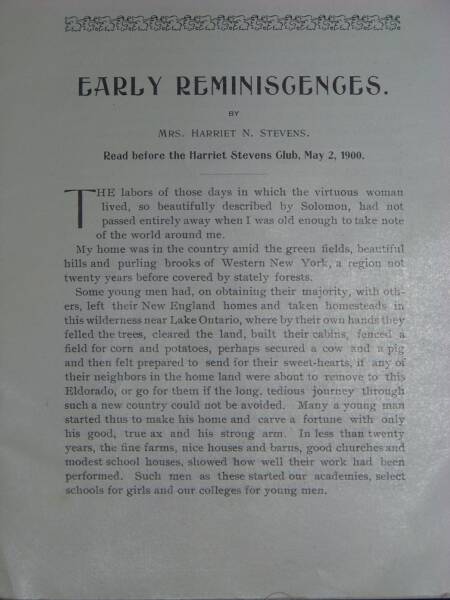

Read before the Harriet Stevens Club, May 2, 1900.

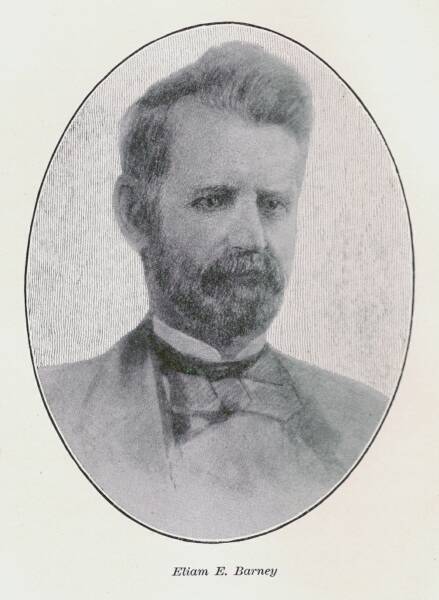

My own introduction: Harriet Newell Barney Stevens was born April 25, 1818 in Henderson, Jefferson County, New York. She was the daughter of Benjamin Barney and Nancy Potter, and as such the sister of Eliam Eliakim Barney (better known as E.E. Barney early Dayton educator and founder of the Barney-Smith Car Works). Harriet, was called to Dayton by her brother to assist in the education program at the old Academy, and then at Cooper Seminary, and still later at Central High School. She was the wife of Ansel Edmond Stevens (A.E. Stevens) who was one of the five men involved in the corporation of Barney-Smith in 1867. The following are her recollections of life in western New York state where she and E.E. were born and raised.

Harriet's brother Eliam E. Barney

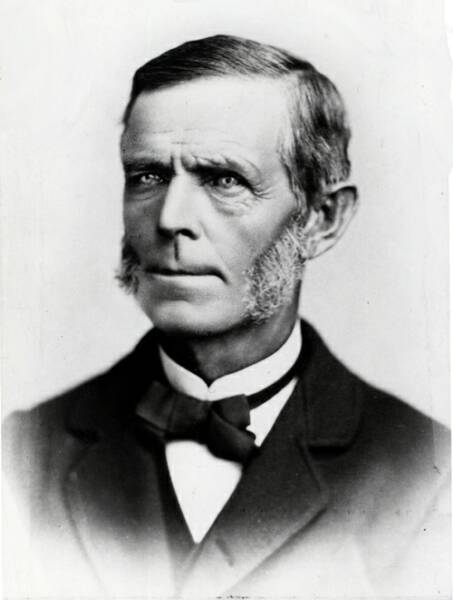

Harriet's husband Ansel E. Stevens

"The labors of those days in which the virtuous woman lived, so beautifully described by Solomon, had not passed entirely away when I was old enough to take note of the world around me.

"My home was in the country amid the green fields, beautiful hills and purling brooks of Western New York, a region not twenty years before covered by stately forests.

"Some young men had, on obtaining their majority, with theirs, left their New England homes and taken homesteads in this wilderness near Lake Ontario, where by their own hands they felled the trees, cleared the land, built their cabins, fenced a field for corn and potatoes, perhaps secured a cow and a pig and then felt prepared to send for their sweet-hearts, if any of their neighbors in the home land were about to removed to this Eldorado, or go for them if a long, tedious journey through such a new country could not be avoided. Many a young man started thus to make his home and carve a fortune with only his good, true ax and his strong arm. In less than twenty years, the fine farms, nice houses and barns, good churches and modest school houses, showed how well their work had been performed. Such men as these started our academies, select schools for girls and our colleges for young men.

"Young as I was, I felt the wave of enthusiasm that some of these enterprises created. In this battle of life the men were nobly seconded by their wives and daughters. Like the "virtuous woman" they laid their hands to the spindle and their hands hold of the distaff, they spun wool and flax and worked willingly with their hands. They too, arose while it was yet night to give meat to their household, for breakfast was seldom later than five o'clock, if so late, and they like her, clothed their household in scarlet, a favorite color of the young. Their husbands and sons were seen in the gates in clothes of their own manufacturing. There had not occurred then, only in a small way, that division of labor which has since resulted from the increase of commerce and the establishment of manufactories.

"Let us look into one of these old-fashioned homes. We will enter the spacious kitchen so well lighted. How clean the floor! Everything seems so sweet and cheery; no odor of cooking anywhere. Why, there is no cook stove. That immense open fire place with its swinging crane, and that oven so nicely hidden by that door which seems a part of the finish of the fireplace, does the cooking. Now you see why the air of the room is so sweet. That immense chimney is a grand ventilator. It is doubtful if the food dame ever heard of a cook stove, or if the country had heard of such a thing at this time. The morning is rather cool, let us sit down by this pleasant fire. We shall not in the least disturb the good house wife. She receives all of her callers in her nice kitchen unless it be a formal visit, and then perhaps we may be invited into her "square" room which is not half so pleasant as this bright, airy kitchen. Let us look at this kitchen fire in detail. That back log, two feet through and that big fore stick were put there before the men left for their work. No woman is expected to lift these. The fire between the back log and fore stick which rests on the large andirons is made up of small sticks as needed. What bright tin and pewter on those shelves! Those two large pewter platters, are, I think, heirlooms. Such are not made now. Do look at those potatoes the good house wife is preparing for dinner. Did you ever see such potatoes? The skin almost white and so smooth, no baby's face can be smoother, and those delicate pink eyes. There isn't a mar or a spot on those potatoes, and that pan of apples are just as delicate and perfect as the potatoes.

"Why is it that there are no more such now?

"That insidious fungus had not then found the potato, nor scale, insect or fungus the fruit tree, so you see them in their primitive beauty. Look to what the house wife is doing. With a hook she draws the crane toward her and takes the cover from a very large cooking pot, which is suspended by a hook from the crane. Now for the first time we catch the smell of cooking meat as she removes the cover from the pot. A piece of the sweetest corn beef and pickled pork have been cooking for an hour or more in this pot over the fire. Now she adds some cabbage, turnips, and these nice potatoes to be cooked with the meat. Yes, and a bag pudding too, which resembles a bag of table salt. All is now covered up and swung back over the fire. The table is set with a deep blue ware that contrasts so well with that white home-made table cloth. There is something peculiar about this ware, a portrait in the center of every dish besides the ornamentation around the edge. Who is it? This ware is made in honor of the last visit of Lafayette to our country. A band encircling his picture bears the words, "Lafayette, Our nation's guest and our country's glory." He was made the guest of the nation by Congress, and thus in our homes we tried to honor him who had so nobly helped in our struggle for independence. But we must go back to our hostess. It is baking day and the bread is nearly out she has to make a short-cake to eke out. She has taken out her bake kettle. A large flat bottomed kettle with legs three or four inches long. Now she places this upon some hot embers on the hearth, and proceeds to make her cake, by either making some weak lye from the hot ashes or dissolving some pearl ash, for there is no baking soda or baking powder in these days, pouring it in some sour cream and mixing quickly with some prepared flour, she rolls out her dough, crosses it in diamonds with a two tined fork, carefully pricking the center of each, and after placing it upon a round tin, puts into the bake kettle, covering with a close fitting cover which is also covered with hot embers. Now she blows the horn which is a welcome sound to the men in the filed. While waiting their coming she adds a plate of golden butter to the table, cheese of her own making and some rich cream sweetened with maple sugar for her pudding. Little besides maple sugar, which is abundant, is used in these days.

"While the men lave their faces and comb their hair, the good wife takes up the dinner. In the center of one of those large platters is placed the beef and pork garnished with the turnips and cabbage. Those beautiful potatoes must have a dish to themselves. The short cake is taken from the bake kettle and broken in suitable pieces, never cut. The pudding is turned out of the bag with a smooth, shining skin. By the way, did you ever hear about that Connecticut woman that made a bag pudding that turned over a load of hay and killed a man? That young man that finished his dinner before the rest, has gone into the back yard to prepare the oven wood. He sees the signs of baking day, and is striving for the good graces of the mistress, who has some lovely daughters who are considered experts in spinning and weaving. He knows the old saying about the "man that gets good oven wood." There, he has brought it in. I think he would start the oven, but all are going to that stream yonder and he must leave. The house wife opens that door that seemed to be part of the mantle, we see a large brick oven with an iron mouth, closed by an iron door. This she opens and puts some live coals in the center of the oven., on which she lays the wood already prepared. This she soon brings to a blaze with a pair of hand bellows if she has them, if not, she blows and blows with her mouth until her face swells and eyes redden and patience nearly expires. If this poor woman only had a match, just one little match, how quickly her troubles would be over. But no, she can't have one yet; wait twenty or more years and some one will bring you a match. If no one in the whole City of Dayton could get a single match in the next twenty-four hours, the twenty-four hours following would be spent in raising a monument to the man who invented matches. We would then realize what that nameless man had done for us. The fire has finally started in the oven and it is burning like a furnace. Now the good house wife moulds out her bread, makes her pies of apple and custard, six or eight of them. Pies appear at nearly every meal; so common they can scarcely be called dessert. Now she prepares a basin of beans for the oven and a pan of apples; by this time the fire is burned down and the oven is hot. The coals are removed by means of a long handled shovel. This is indeed hot work. When with bare hand extended into the middle of the oven she can slowly count ten, she puts in the loaves of rye and indian bread and the basin of beans, and when she can count twenty the wheat bread and the rest of her baking. In an hour the baking is removed excepting the beans and the "rineinjun" bread which remains in the oven until the next morning to be warm for breakfast.

"We will take leave of our good dame and pass out through the back porch where her two pretty daughters are dipping candles. O, what quantities. How many? Twenty dozen; enough to last through the summer. Can't you use kerosine [sic]? Never heard of it. The tallow candle is all of the light of these days, a pretty good light too, when well made. How do you light your meeting house? Each family takes a candle in a lantern already lighted and we light from that. When all get there the room is quite bright. We do not have evening services often.

"Let us follow those merry sounds we hear from that stream yonder. What shouting! This is the great gala day for the boys. The spring planting and plowing are over. The farmer with his sons and hired men are at that temporary dam washing their sheep. The excitement runs high, the fun is great as one woolly fellow after another is forced into the stream for his annual scrubbing. That surly looking one with those large curling horns, resents this rough usage. Sharply eyeing his antagonist, with a well aimed butt lands his would be washer in the stream. Screams of laughter greet this performance, while the dripping washer man rising quickly from his forced bath, soon teaches those curling horns that he is their master.

"While this is going on, at the house the good dame with her daughters have allured the flock of geese into the stable, where clothed with big aprons, towels pinned tightly about their heads, they each secure a bird, drawing an old stocking over its head to prevent their nipping bites, proceed to remove the ripe feathers. This is called picking the geese, which has to be repeated two or three times during the summer. In this way the good house wife replenishes her beds and provides an outfit for her daughters when they go to homes of their own.

"Three days after the sheep washing, comes the sheep shearing which may last several days if the flock be large. As soon as a fleece is removed the wool picking begins. Now young maids and old ones are busy the whole day long removing sticks and burs from the fleece and pulling apart its matted points. Day after day this goes on until her stock of wool is ready for the carding machine. All this over the busy house wife prepares for haying and harvesting. No mowing machine in those days or reaping machine that cuts, threshes and puts into bags, the grain as it is driven leisurely through the ripened fields, but strong men with step firm and steady, swing the scythe to fell the grass or cradle the grain with that rythmic [sic] motion that gives you the sense of measured verse.

"These are followed by the pitchers, rakers and binders, lastly the water carriers. This office generally falls to the younger boys, too small to rake. Weeks elapse before the harvest is all housed and the extra hands dismissed. Before all this is accomplished, the wool carded into rolls is brought home from the carding machine, and spinning begins. The whir, whir, of the wheel is heard now from early morn until dewy eve. Soon large bunches of yarn hang from the hooks in the spinning room. The scouring of yarn and warping of web are next in order. The loom is set up, the swifts, reel and quill wheel are brought out. If all this is going on in one room, as it sometimes was, as you listen to the band, bang, of the loom, the constant whir of the wheel, you may wonder where Solomon found all that beautiful poetry with which he surrounded his virtuous woman. Solomon’s ears were not pained by any such medley of sound. These noises are the result of inventions since his time, to speed the work. His virtuous woman sat at the loom as do the Navajo Indian women of today to weave their wonderful blankets. Those ancient looms are almost fac similes of hers, and she wove her silk and purple and fine twined linen and tapestries in the same patient manner. There was good reason for her candle not going out by night. If we worked faster and harder and made more noise than she, it was after all, the same heart love that planned and performed these labors so lovingly and cheerfully for our loved ones.

"Can you imagine the happiness and pride of our mothers as they looked upon their children clad in the comfortable garments they had spun and woven for them? Was it not with a deeper love she covered her little ones at night in the nice bed, every part of which was the result of her own efforts?

"We will not blame the pride she felt in the new mill dressed suit worn by her husband, spun and woven under her own eye. Pardon a personal reminiscence of those early days. Well, I remember when my oldest brother, E. E. Barney, was in college, how carefully the yarn from the finest of wool was spun and woven for his clothes. My mother, fearing the clothier, who was to dress the web like broad cloth, would not be sufficiently careful in dying a deep fast blue, colored ever skein with her own hands before it was woven, after which it was sent to the mill to be fulled and dressed. In 1835, several years after, that same suit of clothes, here in Dayton, was made over for my ten year old brother for his Sunday suit. I remember how well it looked on him.

"Such was the necessity for constant labor that most of the amusements of the young were connected with corn huskings and apple parings, quiltings, &c., the young people meeting at their different homes of evenings to perform these labors. Many were the merry jokes and mischievous glances when the one who removed a paring without a break was challenged to whirl it three times about their head, then let it fall to see what letter it would make. Many too, were the blushes of the maiden, when her partner in husking showed the red ear of corn which he had found. Such parties had one great advantage, each one knew what to do with his hands.

"How strange to think all this idyllic life which has lasted so many years has been swept away in my life time. Even the knitting which filled the idle moments, is gone too. The harvest of grain and fruit gathered, the household clothed, the winter's wood in the shed, the children are sent to school in the little read school house found in almost every neighborhood. The house wife has now a little rest, at least comparative rest. The men in the barn are threshing out the grain with tramping horses or thumping flail. The long winter evenings give time for the social life of the family. Gathered about the ample fire-side, a pitcher of cider, a plate of apples and doughnuts at hand, they told stories, guessed riddles and proposed conundrums, discussed the news found in the weekly newspaper, all of which was believed because it was found in the newspaper, sang songs and hymns until the time of retiring brought the evening worship. The Christian father of those days, as busy as he was, took plenty of time for family devotion. Spelling matches and sleigh rides for the young people gave variety, sometimes, on moonlight nights.

"The threshing over, February brings the flax break and swingle tree on the sunny side of the barn. In the house all the paraphernalia of spinning and weaving again appear. Little wheel for flax, hackle, one or two pairs of cards are the additional instruments required for this new work. Hatcheling, carding, spinning and weaving, fill every spare moment from general house work.

"Often the first green grass of spring is covered with yards of table linen and sheeting to bleach in the sun and dew. Then, as now, every house wife desired a large store of these goods for herself and each of her daughters. Summer clothing for men and often for women, was made from this flax. I remember how my well ironed, linen dress of blue and tan check shone, that I wore in my childhood. Handkerchiefs were woven too, sometimes. To be accounted the best spinner and weaver in those days was as great an honor as it is now to be accounted the best musician. It is told of one young woman that she spun and wove her own wedding dress and to prove the fineness of the thread drew every skein used in weaving it through her thimble. This made 800 threads passing through her thimble at once. Her dress must have been the same as linen lawn. Calico and gingham were imported goods and of a very fine quality. Prices ranged from twenty-five to seventy five cents per yard. Every scrap of any size was carefully preserved, and to give your dear friend a piece of your new dress was as much a compliment as it is now to give her your photograph. One of these pieces would remind you as vividly of your friend as one of her pictures. With what beautiful and intricate designs were these pieces put together for the stock of quilts each young woman felt she must have on leaving home. It was in such work she studied form and color. I have been interested in observing how different the designs in the quilts I have seen in the North and in the South.

"It is told of Mary Lyon, the founder of Mount Holyoke Seminary, that she earned the money for the beginning of her higher education by spinning and weaving. If she herself warped and put in loom and wove the figured table-linen and bed spreads in the various patterns, we can understand how she acquired that wonderful concentration of mind that enabled her to recite all of Alexander's Grammar after four day's study at one lesson.

"To put the threads of the web properly through the several sets of harness to produce the desired figures, and touch with the feet in proper order the treadles, four or six in number, which move the harness, throw the shuttle and keep the eye on every thread to see if any break, requires no ordinary effort of the mind. As few could do this work then in proportion to the number of workers, as can now distinguish themselves as scholars among students.

"I have given only an outline of these home labors in the early days of our country. So many things had to be made by hand, because they could not be bought, that ingenuity and invention were in constant exercise. It was this practical kind of thinking and working necessitated by the age in which they lived that made those strong men and women which made our country what it is. I will not say that in the former days were better than these, though I confess to a very loving remembrance of them. That can only be determined by which days produce the nobler men and women. It is character and not wealth that is to be placed in the scale. Whether or not we excel them let us ever keep in loving remembrance the labors and self denials of our noble ancestors. They paved the way for what we now enjoy. We reap the results of their sweat and toil.

"In all new countries the farming community is necessarily the more prominent until food and clothing are abundant. This state the country gradually attained through the peace which followed the war of 1812. Factories multiplied and commerce increased. Farmers now found it for their interest to dispose of the raw material instead of working it up at home,. By the year 1830, the wheel and loom seldom left their hiding place

in well-to-do families, until they became the objects of the curiosity hunter. Labor saving inventions soon began to lessen the labor of both sexes. I could wish the cheese factory invention had been omitted in the interest of the better butter and cheese those early times gave us. In those early days the school mar reigned supreme during the three summer months in the little red school house, with its small vestibule in front called the entry. Here are hung our wraps before entering the school room, which must always be entered with a bow from the boys and a low curtsy from the girls to the teacher who sat behind her desk, which was on a low platform at the opposite end of the room. She taught reading, writing, geography, working samplers and a little embroidery. She was in some districts a great personage, who received a $1.00 or $1.25, sometimes $1.50 per week for wages; boarded from three days to two weeks according to the number of pupils each family sent. Not many children over ten years of age went to school in summer. In winter, when the school master came, all excepting those who could go to the Academy, went to the little red school house.

"The geography and atlas of those days would be a curiosity compared with those we now have. All but two of the states in our Union were east of the Mississippi. The region marked territory was larger than the settled portions of our country. Africa was little more than fringed by the parts known. Our oceans seemed so vast then. How big the world was, as we thought of the three long years required by Captain Cook to sail around it, and how diminutive has steam made it, by belting it in eighty days.

"Letters in those days were not carried by weight, but by the number of pieces of which they were composed. However large the sheet made no difference. Envelopes could not be used, but the letter must be so written that it could be folded without an envelope. The receiver paid the postage on all but business or love letters, which was twenty-five cents for 400 miles, eighteen cents for 300 miles, &c. The change came gradually to the present. It is a little over fifty years since the law required letters to be sent by weight. The postage was at first reduced to ten cents and then three, finally as we now have it.

"About 1840 occurred one of those feats of chemistry that caused much wonder then. It was fixing permanently the reflected images of objects by means of chemicals. It is wonderful still in the perfection to which it has been brought, and how this photography has increased our knowledge of the world and the heavens too. The spectroscope a later invention, how it has overturned theories.

"Twenty years ago a scientist stated that seventy-two cups would contain all the different elements that make up our world. What will he call an element now, since the spectroscope has been brought to bear upon the contents of these seventy-two cups?

"You imagination must fill the spaces I leap over in the field of invention. The world hardly becomes adjusted to one discovery before it is put agog by another and greater one. If we can tell where we are today, who can tell where we will be tomorrow? The lightning that rifts the clouds and rends the earth today, is tomorrow made to tick a message to a friend, and another day bring the very tones of his voice to our ear, and then as our humble servant carries us through our streets, lights our way, illumes our homes. Lightning and steam annihilate space and move the world, for they carry thought everywhere. What wonders are to be accomplished by those X Rays of light, or that stream of frozen air, are not yet determined. These new forces are not yet reckoned with; all that they may become the world is not yet seen. When and where will all of these changes end? Will the world ever become staid and settled? He only can answer who can measure mind. Not one mind but generations of mind, for each generation of mind takes its stand upon the heights attained by previous minds and reaches out farther into the realm of nature.

"Will some dark cave be found in this realm, having written over its entrance, "Thus far but no farther?"

Early Reminiscences by Harriet Barney Stevens on left. Twentieth Century Christianity by David M. Rowe on right.

Early Reminiscences pages 2-3

Early Reminiscences 1st page.

The photographs and information gathered on this site are the property of Linda Trent

All rights reserved.©